The Hemlocks of Southern Appalachia A Keystone Species Facing Extinction by Exotics

by Erik Gerhardt

Southern Appalachia’s forests, some of the most biologically diverse areas on earth, are under attack by yet another wave of non-natives. While admitting that the unnatural losses incurred over the last 75 years—including the American chestnut, elms, Fraser fir and others—have been nothing short of devastating, the demise of the hemlock stands to be the region’s most catastrophic casualty yet.

Introduction of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid to Southern Appalachia

Now, in particular in Southern Appalachia where mild winters do little to suppress the adelgids, centuries-old hemlocks are dying in shocking numbers and over ever-shortening intervals. The hopeless prognosis for untreated hemlocks after initial infestation has steadily decreased as the adelgid has migrated south. What was once commonly cited as a 6-8 year survival expectancy has now been reduced, often times, to just 3 years or, occasionally, a mere 2.

The Hemlock Woolly Adelgid: A Pest Leaving a Path of Destruction

The accelerating cycle now sweeping across Southern Appalachia begins anew when the HWA hitches a ride on the feet of birds or on wind currents; on deer or smaller mammals; on humans or our gear; or in truck beds and trailers carrying shipments of infested nursery stock. Shortly after being transported to its new host, the HWA attaches to the base of a hemlock needle and begins feeding on the tree’s stored starches. Meanwhile, the adelgid secretes a protective cover for itself and its eggs called ovisacs. It is this sticky substance, plainly visible in the photo as little cotton-like masses, which is the first indication of infestation. Signs of serious decline become evident over the next year or two as the hemlock’s unique, deep green tone turns to dull gray. This is accompanied by a shedding of needles that moves progressively up the tree, leaving a stark, emaciated, lifeless frame. Additional size affords no additional defense. Even the largest of hemlocks succumb in a startlingly short period of time.

The Natural Range of the Hemlock and the 2005

Distribution of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

A Disaster of Our Own Making

The unique form, setting and ecological role of Southern Appalachia’s hemlocks are inescapable. Within Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP) a 2001 study found the hemlock to be the second most common tree, with nearly 17% of the park’s 520,000 acres featuring a “significant hemlock component.” Meanwhile, the National Forest Service estimates that the hemlock constitutes 10% of western North Carolina’s forests. The figures are especially impressive when one considers the number of trees—up to 130 species—vying for space in this biologically diverse region. Yet for all that diversity, there is no similar species that can move in and help provide some semblance of ecological balance in the hemlock’s absence. Both of the region’s hemlocks, the eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) and the Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana), possess no natural resistance to the HWA. Additionally, because the HWA attacks and destroys both young and old trees alike, the hemlock is left no means of regeneration.

A Defense of Our Own Making

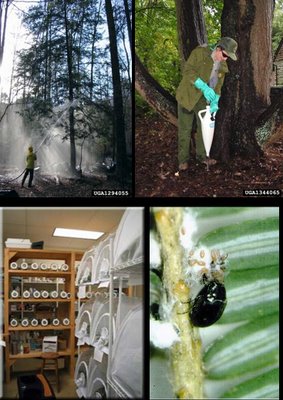

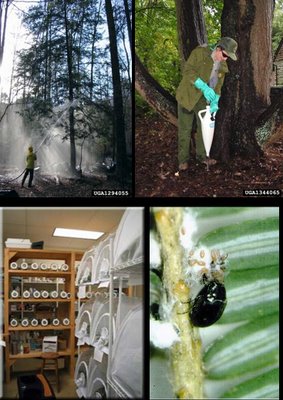

The strategy for defending a tiny fraction of the region’s hemlocks utilizes three different agents. For roadsides and other developed areas, a soap or oil solution that dries out the adelgids is delivered via high-pressure sprayers capable of saturating entire trees. Other areas are treated with a systemic pesticide, imidacloprid, which is either injected into the ground or, when there is concern that the chemical could contaminate a water source, injected directly into the trunk of the tree. The chemical injections, once largely dismissed as impractical for wide-range use, are being increasingly plied as a stop-gap measure, in particular in GSMNP where so many great hemlock forests are being rapidly decimated. Still, the long-term survival of our hemlocks, in particular those in more remote areas, depends largely on a combination, or cocktail, of predator beetles that feed exclusively on the adelgids. These beetles, native to the same region as the adelgid, are being reared in a handful of labs around the South.

Hemlock Form

The eastern hemlock is often called the redwood of the East, and it is an easy association to make. While prevalent throughout the Northeast U.S., the southern portion of Eastern Canada and much of the Great Lakes States, it is here in Southern Appalachia that the hemlock achieves its greatest development. On occasions exceeding 18 feet in circumference (measured 4 ½ feet above the ground on the tree’s upslope side) and approaching 170 feet in height, no evergreen in the East can rival the hemlock for volume. It is also among the longest-lived of the indigenous trees in its range, the record-holder having survived an amazing 988 years. Giants throughout Southern Appalachia regularly surpass 400 years of age and, occasionally, even 500 years.

The eastern hemlock is often called the redwood of the East, and it is an easy association to make. While prevalent throughout the Northeast U.S., the southern portion of Eastern Canada and much of the Great Lakes States, it is here in Southern Appalachia that the hemlock achieves its greatest development. On occasions exceeding 18 feet in circumference (measured 4 ½ feet above the ground on the tree’s upslope side) and approaching 170 feet in height, no evergreen in the East can rival the hemlock for volume. It is also among the longest-lived of the indigenous trees in its range, the record-holder having survived an amazing 988 years. Giants throughout Southern Appalachia regularly surpass 400 years of age and, occasionally, even 500 years.

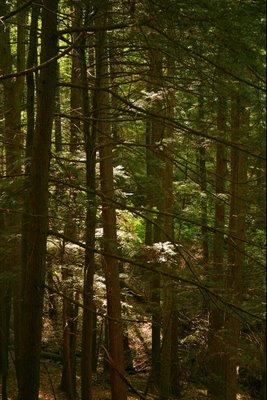

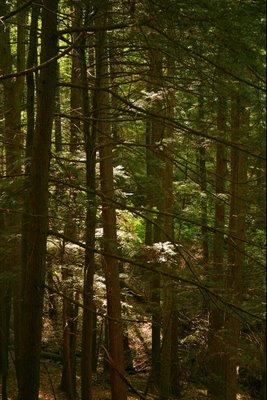

Perhaps even more amazing is the hemlock’s capability to bide its time in an understory role. Studies have shown that the tree can withstand suppression for as long as 400 years, surviving on as little as 5% of full sunlight. That makes the eastern hemlock the most shade tolerant of all tree species, the necessity of which is apparent in the accompanying picture taken in Obed National Wild and Scenic River on the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee.

The hemlocks in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park have been all but wiped out by the hemlock woolly adelgid. Of the few that remain, most are heavily infested. Pictured here, however, is a weather-pruned, lone dwarf atop Old Rag—a survivor from the beginning. Few trees can match the inspiration of a determined hemlock, hanging on and adapting despite seemingly inhospitable circumstances. For the forms of natural hardship the hemlock can handle it may well be peerless, equally adept at establishing a foothold in almost absolute shade or while facing constant exposure in the tiniest of rock crevices.

The Carolina hemlock, a smaller tree with a much smaller range, flourishes in the face of such challenging footholds. Because of this trait, the Carolina hemlock is likely nowhere more obvious or inspiring than in North Carolina’s Linville Gorge. In populating cliffs, outcroppings and boulder fields, the Carolina hemlock commonly takes on fantastically bizarre forms.

If ever a tree has exemplified gracefulness, it is the hemlock. That soul-stirring quality is especially profound in winter. Smaller hemlocks transform snowfalls into wonderlands and generously splash heartwarming greenery over otherwise stark winter woods.

Hemlocks, rhododendron, a mountain creek—they are the trinity of Southern Appalachia. Those three components are central to so many classic scenes throughout the region. There is no more common, more beautiful, more therapeutic combination in Southern Appalachia. Likewise, there can be no more thorough, more heartbreaking, more sickening loss. Pictured here is Gee Creek in the southern portion of Tennessee’s Cherokee National Forest. The gorgeous hemlock shaded gorge is not unlike countless others, though it is increasingly rare to find such places still free of the hemlock woolly adelgid. Chances are Gee Creek will soon be added to that ever-growing list, as the adelgid is widely prevalent in a neighboring county.

Hemlocks, rhododendron, a mountain creek—they are the trinity of Southern Appalachia. Those three components are central to so many classic scenes throughout the region. There is no more common, more beautiful, more therapeutic combination in Southern Appalachia. Likewise, there can be no more thorough, more heartbreaking, more sickening loss. Pictured here is Gee Creek in the southern portion of Tennessee’s Cherokee National Forest. The gorgeous hemlock shaded gorge is not unlike countless others, though it is increasingly rare to find such places still free of the hemlock woolly adelgid. Chances are Gee Creek will soon be added to that ever-growing list, as the adelgid is widely prevalent in a neighboring county.

Pictured here, the trinity of Southern Appalachia as seen along the banks of Deep Creek on the North Carolina side of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. This wonderful watershed is heavily infested and seeing significant mortality. Like other affected areas, there is concern that the loss of the hemlocks will lead to nitrate leaching, producing an environmental domino effect.

Hemlock Function

Countless miles of Southern Appalachian streams are lined and shaded by hemlocks. No scene is more instantly identifiable with the region. The trees prevent erosion, insure stream flow in times of drought and maintain favorable conditions for salamanders. The shade provided by hemlocks means water temperatures remain cooler in the summer—as much as nine degrees Fahrenheit. This function is vitally important where brook trout—the region’s only native trout—and aquatic insects are concerned. Pictured here, the placid water of Georgia’s Conasauga River reflects the deep shade afforded by streamside hemlocks.

Dozens of bird species utilize the hemlock, including Wild Turkey and Ruffed Grouse. Particularly dependent birds include Wood Thrush, Louisiana Waterthrush, Acadian Flycatcher, Canada Warbler (top left), Blackburnian Warbler, Black-throated Green (bottom left) and Blue Warblers, Dark-eyed Junco (top right), Blue-headed Vireo (bottom right), Red-breasted Nuthatch, Veery and Northern Goshawk. In Tennessee alone, it is estimated that 90 species of birds and mammals are ecologically tied to the hemlock.

The hemlock accommodates untold numbers of fungi, mosses and lichens. Among larger plants strongly associated with hemlock is the endangered piratebush. From its buttressed base to its lilting crown, the hemlock sustains a tangled web of life. From cornerstone to capstone, there is no denying the hemlock’s keystone qualities.

HemlocksBefore and After the Adelgid

The photo below is of Cane Creek Gorge on the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee. Notice in this springtime shot the way in which the numerous hemlocks, with their luxuriantly dark-green tone, stand out in contrast to the lighter, still-emerging leaves of the deciduous trees. This area thankfully remains uninfested.

This comparison “after” photo is of Linville Gorge along the Blue Ridge Front in North Carolina. Here, a short distance downriver from the Blue Ridge Parkway and wildly popular Linville Falls, dead hemlocks appear as gray masses. In a sad reversal of nature, the evergreen's extensive presence is evidenced by its contrasting barren appearance. Great stands of eastern and Carolina hemlocks are being decimated in the gorge; forests that largely escaped logging due the ruggedness of the area.

Pictured here is a healthy eastern hemlock branch from the Kentucky portion of the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area.Notice the numerous clusters of new growth. This part of the Cumberland Plateau is believed to still be free of the hemlock woolly adelgid.

can never develop a resistance to its slayer.

The State of Southern Appalachia's Hemlocks

In Southern Appalachia there is no escaping the hemlock. Regretfully, it is getting to where the same assertion could be made in regard to the adelgid. Certainly, there is no escaping its looming threat, and in many places, there is no denying its devastating toll.  The ancient hemlocks in Shenandoah National Park’s (Virginia) once enchanting Limberlost were destroyed in just a few years. Afterwards, the park service chose to cut them down as a matter of public safety. Such measures are not inexpensive. In Great Smoky Mountains National Park it currently costs approximately $150 to remove a hazard tree fifteen inches in diameter. Meanwhile, the protective treatment for such a tree runs about $19.

The ancient hemlocks in Shenandoah National Park’s (Virginia) once enchanting Limberlost were destroyed in just a few years. Afterwards, the park service chose to cut them down as a matter of public safety. Such measures are not inexpensive. In Great Smoky Mountains National Park it currently costs approximately $150 to remove a hazard tree fifteen inches in diameter. Meanwhile, the protective treatment for such a tree runs about $19.

Pictured here is a trailside bench in Shenandoah’s Limberlost. Where a decade ago one might have sat and contemplated man's smallness in the big picture, one's thoughts today tend towards man's huge impact over such a small span of time. In the upper portion of nearby Whiteoak Canyon the damage is equally dense. There, however, the hemlocks are left to fall in their own time.

This photo was taken along the world-famous Appalachian Trail near Fishers Gap in Shenandoah National Park. Such greatly disturbed areas are ripe for all sorts of invasive exotics. This vicious cycle is now commonly occurring in Shenandoah where more than 90% of the hemlocks have been destroyed.

Ramseys Draft Wilderness in Virginia’s George Washington National Forest was, until recently, one of the region’s great old-growth cathedrals. Hemlock mortality here rivals that of Shenandoah National Park. Far fewer people, however, know of the devastation that has occurred. Occasionally, articles will appear describing Ramseys Draft as though its towering hemlocks are still blocking out the sun.

This photo, taken in October, 2005, features a stand of Carolina hemlocks high on Flat Top at the Peaks of Otter, just off the Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia. The Carolina hemlock’s entire range, from Tallulah Gorge in northern Georgia to the James River in central Virginia, is now infested. While still healthy in appearance, even this small, isolated stand had been discovered by the adelgid.

In West Virginia’s New River Gorge National River, this healthy hemlock forest is now threatened as a result of the adelgid’s arrival. The spring of 2006 saw the first limited-response treatments in this area. The NPS was assisted in these efforts by the Citizens Conservation Corps of West Virginia. The New River Gorge National River, Gauley River National Recreation Area, and Bluestone National Scenic River received chemical treatments “at important visitor sites and sensitive wildlife habitats.” Additionally, predator beetles are being released at New River Gorge and Gauley River. Some hemlocks in the gorges are up to 350 years old.

A classic setting on the Cumberland Plateau of Kentucky, Tennessee and northern Alabama features eastern hemlocks at the heads of hollows, growing atop and just below the endless sandstone bluffs. The scene pictured here is Yahoo Arch in Kentucky’s Daniel Boone National Forest just outside the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area. The hemlock woolly adelgid was detected in Kentucky for the first time in the spring of 2006. This initial infestation was reported in Harlan County, ominously close to Cumberland Gap National Historic Park.

Linville Gorge in North Carolina’s Pisgah National Forest represents one of the most substantial old-growth preserves in the East. Tragically, the hemlock woolly adelgid is rapidly laying waste to both eastern and Carolina hemlocks. It might be argued that as a percentage of its overall forest, no place stands to lose more than rugged, renowned Linville Gorge. The worst of the damage is mostly limited to the upper or northern half of the gorge, but the adelgids are omnipresent.

Farther south in the Pisgah Ranger District, hemlock decline, while widely obvious, is not as widely advanced. This photo, with a full bushy Carolina hemlock framing Looking Glass Rock, was taken in June, 2006. Notice that the tree’s needles grow in a whorl, whereas the needles of an eastern hemlock grow in a flat plane. The other Carolina hemlocks in this area atop John Rock were in very poor shape. Meanwhile, the eastern hemlocks along the streams in nearby Shining Rock Wilderness are dead or sparsely needled, but to the south in DuPont State Forest, the adelgid’s presence hasn’t yet diminished the appearance of the trees.

This photo showing destroyed, gray-ghost hemlocks was taken in May, 2006 from an overlook above Cataloochee (North Carolina) in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Will Blozan, who has discovered and documented numerous national champion trees in the park and elsewhere, has termed Cataloochee “The Valley of the Giants”. All of the trails here lead through incredible old-growth forests. Most are in exceedingly poor health. The park treated the Boogerman Trail with chemicals in 2005 when funds first became available, but in many places the trees were already on the brink of death—just three short years after being initially infested. Too little, too late: it is the cycle that has accompanied the adelgid most everywhere it has landed.

All drainages in Great Smoky Mountains National Park are infested, but across the park’s 520,000 acres, the health of the hemlocks varies significantly. For example, the hemlocks pictured here are showing substantial crown thinning but are still strong candidates for treatment and recovery.

Greenbrier, on the Tennessee side of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, is another area with extensive old-growth. Hemlocks along the Brushy Mountain Trail (pictured here from March, 2006) were chemically treated by the park service before the adelgids had thoroughly weakened the trees. Excepting the upper portion of the trail where the hemlocks are significantly impacted, most of Brushy Mountain is still an unforgettably delightful experience.

Greenbrier, on the Tennessee side of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, is another area with extensive old-growth. Hemlocks along the Brushy Mountain Trail (pictured here from March, 2006) were chemically treated by the park service before the adelgids had thoroughly weakened the trees. Excepting the upper portion of the trail where the hemlocks are significantly impacted, most of Brushy Mountain is still an unforgettably delightful experience.

One of the most heartbreaking losses to date occurred in South Carolina’s East Fork drainage. The photo below was taken in May, 2005 when the majority of the great hemlocks were dead. These towering boles in the Chattooga National Wild and Scenic River corridor were once part of the tallest hemlock forest ever documented. Knowing that chemical treatments had been proven effective but were deemed impractical or unaffordable, makes the loss of this unsurpassed grove all the more unacceptable.

Throughout the watershed of the Chattooga National Wild and Scenic River (including North Carolina, Georgia and South Carolina) hemlock mortality is common. Pictured below are a pair of eastern hemlocks on the South Carolina side of the Chattooga that have succumbed to the adelgid. There are literally hundreds more of similar stature that have suffered a similar fate. Many of those losses occurred within four years of the area’s initial adelgid sighting in 2001.

Farther east in South Carolina is the hemlock shaded Eastatoe River, one of the most popular trout streams in the state. Cold-water fish, especially this far south, require the cooling shade provided by streamside hemlocks. The photo here was taken in May, 2005 when most of the trees were already severely stressed. In South Carolina, healthy hemlocks are now largely confined to the eastern half of the state’s Blue Ridge Front—the Saluda River basin.

In Georgia, the hemlock woolly adelgid is spreading quickly. Besides the devastation in the Chattooga watershed, more than half of the Chattahoochee National Forest is now infested, while mortality is occurring in as little as two to three years. The Tallulah watershed has also been heavily impacted, with the adelgid arriving in Tallulah Gorge State Park in early 2006. The first beetles produced by a Georgia-based lab (Young Harris College) were released in the spring of 2006, while the University of Georgia hopes to have its larger lab operational in the fall. Georgia Power came through with a critical, eleventh-hour $50,000 donation which prevented the UGA lab from being delayed still another year. Pictured here is Helton Creek Falls, one of the most enchanting settings in all of Southern Appalachia. The large hemlocks which surround the falls and dominate the area are still healthy but heavily infested.

With the great hemlocks of the Chattooga watershed largely decimated, Georgia’s most significant stands of old-growth hemlocks are likely to be found in and around Cohutta Wilderness. The adelgids have not yet been documented within the wilderness boundaries, but they are fast approaching.

The Outlook for Southern Appalachia's Hemlocks

There have been promising advances in the groundbreaking work to combat the hemlock woolly adelgid. Natural predators have been identified, and methods for mass producing these beetles have been fine-tuned; labs have been constructed and staffed; the documentation, planning and implementation of a limited defense strategy have all been accomplished despite severely restricted funding. In the absence of federal and state dollars, the private sector has donated generously to the cause.

The table is set for a full out counter assault on the adelgid, if only the funds for this logical and urgent next step were available. The costs are high, measured either by dollars or by what we stand to lose. While a relatively small group of dedicated professionals work tirelessly to save some of the region’s hallmark trees, time and a lack of money are working against the hemlocks.

In 2004 the National Forest Service spent $1.6 million out of a $4.469 billion budget to suppress the hemlock woolly adelgid in Southern Appalachia. Assume that same year an average American citizen who earned $32,937 (U.S. per capita personal income) purchased a “Save the Hemlocks” t-shirt at a cost of $19. As a percentage, John Q. Public contributed more—about 60% more—of his annual resources to the hemlock cause in Southern Appalachia than did the U.S. Forest Service.

It gets no better where the National Park Service is concerned. For the Great Smokies there was a 2 ½ year wait between the initial adelgid infestation and the park’s first earmarked, adelgid-control departmental funding. The late-arriving $481,000 was, by the park’s own 2004 estimate, only enough to cover 2.3% of the cost to treat all of the park’s hemlocks.

These amazing trees, the ecosystem they support, and the generations of Americans still unborn deserve better.

History will judge our commitment to preservation in Southern Appalachia by the situation now confronting the hemlocks. Additionally, this challenge will set the regional standard for all other environmental issues that follow throughout the twenty-first century. Difficult as it might be to imagine, more is riding on our response than the obvious fate of the hemlocks. We cannot continue at the same funding levels and expect much in the way of results—now or in the years to come.

A Celebration of the Hemlock in Southern Appalachia

The tree for every mood: here eastern hemlocks along Coker Creek in Tennessee’s Cherokee National Forest are resplendent in late-afternoon light. Whether gilded in sunlight, masked in mysterious fog, transformed by a cloudburst into an elaborate emerald chandelier, bowing elegantly under the weight of snow, or frolicking in the face of stiff winds—the hemlock is endowed with a graceful ease, a gift for capturing and reflecting Mother Nature’s moods.

Comers Creek Falls in the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area (Jefferson National Forest) of southwest Virginia represents a classic Southern Appalachian setting. Remove the hemlock and, quite simply, it is no longer the same place.

From Georgia’s Cohutta Wilderness (left) to West Virginia’s Cranberry Wilderness (right) the region’s hemlocks are under siege. Daunting as the threat is, many areas have yet to see serious decline, while still others remain uninfested. Though the window is narrowing, there remains an incredible opportunity to save a sizable percentage of these shade-producing, temperature-regulating, spirit-lifting trees.

One of the most unforgettable scenes in Southern Appalachia is this bottom-of-the-gorge, hemlock-framed view of Fall Creek Falls. Fortunately, Tennessee’s Fall Creek Falls State Park and the much larger Cumberland Plateau have yet to be affected by the hemlock woolly adelgid. Unfortunately, that security could be short-lived. Unlike Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and Michigan, none of the southern states have bothered with hemlock quarantines. Through transport on infested nursery stock, the adelgid has leapfrogged great distances, infesting and destroying other Southern Appalachian forests ten to fifteen years ahead of its projected southerly migration.

Where there’s hemlock, there’s rhododendron—beauty compounded.

Pictured here is a needle-thinned stand of Carolina hemlocks on Brushy Ridge in North Carolina’s Linville Gorge Wilderness.

Pictured here is one of the healthier eastern hemlock groves in Cataloochee, located on the North Carolina side of Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

The unmatched shade provided by the hemlock is exemplified in this inside-looking-out photo taken above Savage Falls in Tennessee’s Savage Gulf State Natural Area.

The region’s enchanting and mysterious hemlock forests: so deep, dark, damp and cool.

Late afternoon: an achingly beautiful time of day to find oneself in the company of hemlocks.

Late afternoon: an achingly beautiful time of day to find oneself in the company of hemlocks.

The branch of a cliff-hugging Carolina hemlock frames Hawksbill, a well-known western North Carolina landmark, and the Linville River far below.

Eastern hemlocks line the banks of Georgia’s Toccoa River near Deep Hole, the put-in for the only designated canoe trail in the Chattahoochee National Forest.

South Carolina’s state-owned Eastatoe Gorge is accessed via a spur off the spectacular 76-mile-long Foothills Trail. The ambitious backpacker could conceivably tour Southern Appalachia—sampling its treasures, personalizing its grandeur—by combining the Foothills, Bartram, Appalachian and Mountains-to-Sea trails. In most areas traversed by those long-distance footpaths—just as in Eastatoe Gorge—the hiker would sadly encounter hemlock woolly adelgids.

The Appalachian Trail stretches roughly 2,200 miles from Georgia to Maine. Along the vast majority of the route hemlock woolly adelgids are now present. Their harmful effect, however, is far greater in Southern Appalachia due to mild winters and the simple abundance of hemlocks, which promotes an increase in the adelgid population. The photo below was taken on the Appalachian Trail just north of Mt. Cammerer in the Great Smokies. Near here in 1957, while marveling at a similar scene, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, a greatly experienced world traveler, professed to Wilderness Society co-founder, Harvey Broome, “This is the most beautiful forest I have ever seen."

Every aspect of the hemlock is unique. Its ecological role, setting, fissured bark, columnar bole, graceful form, dense needles, tiny cones—they all set the hemlock apart, making its prevalence all the more profound. Borrowing from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn”—or one hemlock cone, nestled on and nurtured by one of its fallen predecessors.

A colonnade of unmistakable eastern hemlocks are pictured here from Big Fork Ridge in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. These keystone trees literally support scores of life forms.

The photos below were taken in two of the East’s great old-growth sanctuaries. The waning hemlock on the left inhabits North Carolina’s Linville Gorge Wilderness, while the one on the right resides on the Tennessee side of Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Deep Creek on the North Carolina side of the Smokies is one of the largest hemlock-dominated drainages in Southern Appalachia, much of it old-growth. Celebrated author Horace Kephart set up his final camp along a remote portion of this picturesque creek. Kephart’s love of this forest inspired him to become an outspoken figure in the fight to preserve what old-growth remained through the creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park: "it was always clean and fragrant, always vital, growing new shapes of beauty from day to day. The vast trees met overhead like cathedral roofs. I am not a very religious man; but often when standing alone before my Maker in this house not made with hands I bowed my head with reverence and thanked God for His gift of the great forest to one who loved it. Not long ago I went to that same place again. It was wrecked, ruined, desecrated, turned into a thousand rubbish heaps, utterly vile and mean. Did anyone ever thank God for a lumberman's slashing?” We owe a debt to Kephart, an obligation to preserve what his and other generations have lovingly secured and passed down.

Spring in the North Georgia Mountains

Pictured here are classic, feathery-appearing hemlocks along the swollen Toccoa River.

Summer in the Great Smokies of North Carolina

Pictured here is a grove of towering hemlocks near the lower reaches of Clontz Branch.

Autumn on West Virginia’s Allegheny Plateau

The hemlocks pictured here, complementing and accentuating the fall foliage, overlook the Gauley River.

Winter in the Great Smokies of Tennessee

Pictured here are some of the extensive hemlocks that thrive on the northern slopes of Mt. LeConte.

What Once Was

Pictured on the left, an extraordinarily ordinary eastern hemlock in the tallest hemlock forest ever documented. That forest, surrounding the East Fork of the Chattooga River, is now destroyed. On the right, the Pine Gap Trail in Linville Gorge was once among the most awe-inspiring hikes for old-growth hemlocks anywhere. All of the great trees are now dead or hanging by a thread.

What Is

Threatened but still healthy hemlocks—the most evocative trees in the East—continue to anchor their own unique ecosystems in such places as Georgia’s Cohutta Wilderness (left) and the Great Smokies of Tennessee (right).

What Should Forever Be

A heartfelt thank you for taking time to view this presentation and for your consideration of helping preserve the hemlocks and biodiversity of Southern Appalachia.

The eastern hemlock is often called the redwood of the East, and it is an easy association to make. While prevalent throughout the Northeast U.S., the southern portion of Eastern Canada and much of the Great Lakes States, it is here in Southern Appalachia that the hemlock achieves its greatest development. On occasions exceeding 18 feet in circumference (measured 4 ½ feet above the ground on the tree’s upslope side) and approaching 170 feet in height, no evergreen in the East can rival the hemlock for volume. It is also among the longest-lived of the indigenous trees in its range, the record-holder having survived an amazing 988 years. Giants throughout Southern Appalachia regularly surpass 400 years of age and, occasionally, even 500 years.

The eastern hemlock is often called the redwood of the East, and it is an easy association to make. While prevalent throughout the Northeast U.S., the southern portion of Eastern Canada and much of the Great Lakes States, it is here in Southern Appalachia that the hemlock achieves its greatest development. On occasions exceeding 18 feet in circumference (measured 4 ½ feet above the ground on the tree’s upslope side) and approaching 170 feet in height, no evergreen in the East can rival the hemlock for volume. It is also among the longest-lived of the indigenous trees in its range, the record-holder having survived an amazing 988 years. Giants throughout Southern Appalachia regularly surpass 400 years of age and, occasionally, even 500 years.

Greenbrier, on the Tennessee side of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, is another area with extensive old-growth. Hemlocks along the Brushy Mountain Trail (pictured here from March, 2006) were chemically treated by the park service before the adelgids had thoroughly weakened the trees. Excepting the upper portion of the trail where the hemlocks are significantly impacted, most of Brushy Mountain is still an unforgettably delightful experience.

Greenbrier, on the Tennessee side of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, is another area with extensive old-growth. Hemlocks along the Brushy Mountain Trail (pictured here from March, 2006) were chemically treated by the park service before the adelgids had thoroughly weakened the trees. Excepting the upper portion of the trail where the hemlocks are significantly impacted, most of Brushy Mountain is still an unforgettably delightful experience.